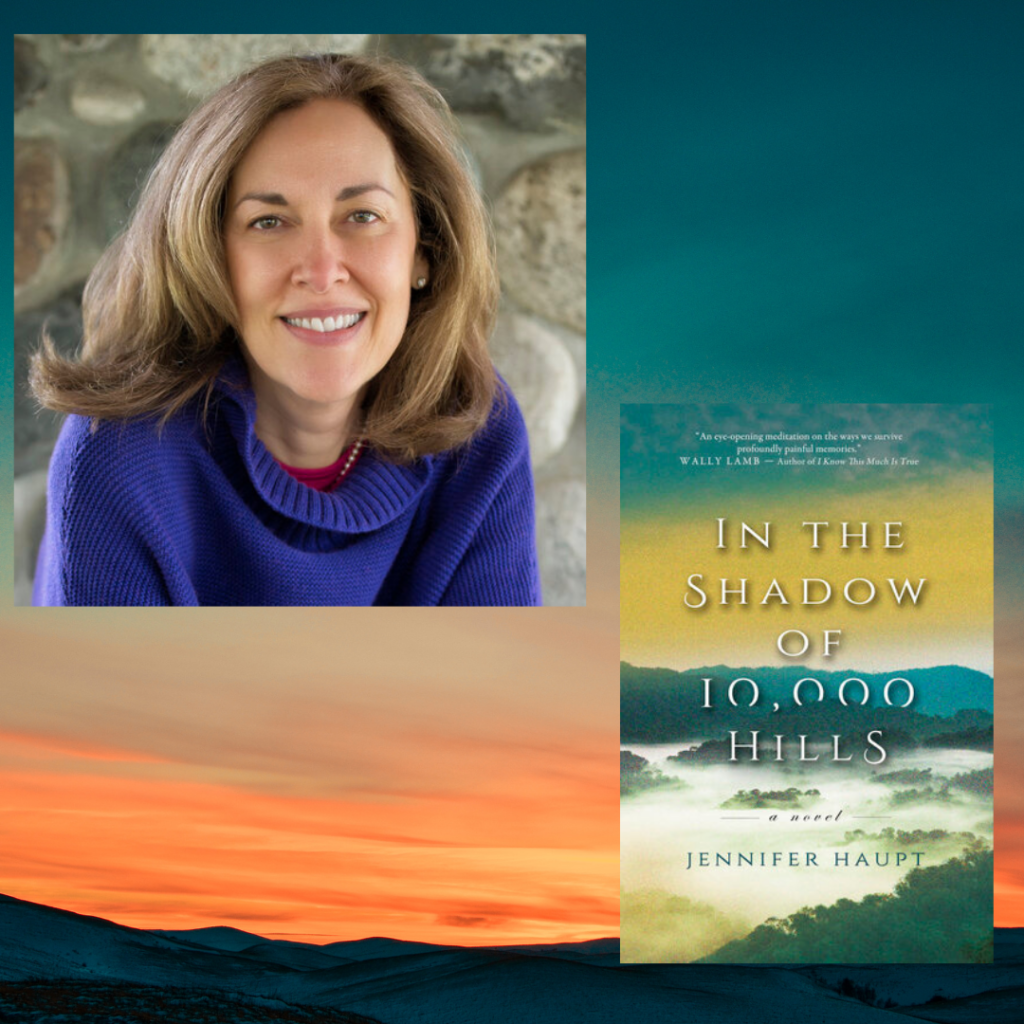

Amahoro, a common greeting in Rwanda, doesn’t exactly translate into English, but is roughly similar to the Hebrew greeting, shalom, says Jennifer Haupt, author of the moving and beautifully written novel, In The Shadow of 10,000 Hills. Like the word “shalom,” amahoro also encompasses the idea of seeking soundness of mind, body, and spirit.

Haupt, who spent a month in Rwanda in 2006, explores these themes in her book, adeptly weaving together several stories: a woman in early 2000s New York, heartbroken after a miscarriage and searching for her father; the lingering wounds in Rwanda caused by the genocide of about one million Tutsi and Tutsi sympathizers by the Hutu militia in 1994; and the 1960s Civil Rights struggles in the U.S.

In The Shadow of 10,000 Hills also explores the idea of grace without forgiveness. Some Hutu perpetrators jailed after the genocide were freed in 2003, due to overcrowded prisons and a lack of qualified judges. That meant Tutsi citizens might now live next to former Hutu militia members who’d killed their loved ones. How could they find some way to live in the same community?

I loved reading this story. It explores the aftermath of a gut-wrenching era in modern history, yet remains full of hope, grace, and insight. In The Shadow of 10,000 Hills also shows how war and conflict can muddy what, at first glance, often seem like straightforward questions of morality.

Jennifer was kind enough to spend a few minutes talking about amahoro, her trip to Rwanda and how it prompted the idea for this novel, and her decision to weave together characters from different countries and time periods. She also provides a glimpse into her next book, Come As You Are, which releases March 1, 2022.

What prompted your trip to Rwanda in 2006?

I was going through something of career crisis. I was tired of everything I was writing about and wanted to travel somewhere out of my normal world.

Also, I’m Jewish, and some of my relatives died in the Holocaust. I felt some kinship with the people of Rwanda, who’d also been through horrors I could never fully comprehend.

Then, there was the beauty of the country. The hills. The gorillas you can’t see anywhere else.

But it was leap of faith. I went not really knowing what would happen. I definitely didn’t expect to come back with an idea for a novel.

What would you like people in other parts of the world, and particularly the U.S., to know about Rwanda?

You know, we ask, ‘why should we care about people in other parts of world?’ But we all go through similar experiences. Connecting with people on an emotional level, understanding their grief and compassion, is important.

Can you talk about your decisions to juxtapose the Rwandan genocide with the Civil Rights era in the U.S., as well as present day New York?

I wanted my book to appeal to people who wouldn’t normally read about genocide and Rwanda. One way was to relate it to our current period in history.

Then I started looking at the character of Lillian, who’s modeled after an expat in Rwanda who runs an orphanage, and was figuring out how would she have connected with Henry (the main character’s father). How would they have developed a romantic relationship? That led to the connection to the U.S. in the 1960s.

Can you talk about the idea of grace in the absence of forgiveness?

All the people in the story have others they’re trying to forgive. Rachel, the main character, is trying to reconnect with and forgive the father who deserted her. Nadine, a Tutsi, had become best friends with a former member of the Hutu military.

So, what happens when forgiveness isn’t possible? Instead, you can let go, and whatever wrong someone has done, is then on them. You don’t always need to forgive. It’s the idea of grace.

In our culture, women in particular are asked to forgive a lot, often when it’s not possible and shouldn’t be asked. That’s the grace of letting go

How do you write about horrific events, yet show the humanity and resilience of those who survived, without becoming maudlin or saccharine?

I worked really hard and asked myself whether the scenes that were hard to read were truly necessary to the story. In the end, there was just one scene that’s difficult. It was important to have that scene, but it wasn’t focus of what I was doing.

For me, it all goes to character development. What does a character want the reader to know they went through?

You’ve mentioned how you enjoy traveling solo. What draws you to it?

I really liked to travel solo when I was in my twenties, thirties, and forties. When I go by myself, I really have to rely on myself. And when I’m with others, I’m not as likely to go out of my way to meet other people. On my own, travel is more reflective and challenging.

Where else would you like to travel?

I still want to go to Thailand. Also, my husband and I have been watching The Amazing Race during COVID. The participants are now in Chile. I’ve been to Mexico, but not other parts South America, and would like to go.

Can you talk about your next book, Come As You Are, which is set against the early nineties music scene in Seattle?

This one is more fun but has the same themes of reconciling with the past and forgiveness. It’s more on a personal level—how to let go of childhood dreams to develop new desires and hopes for your children.

What’s on your TBR right now?

I just downloaded a book by Sally Rooney, Conversations with Friends. I’m also reading Searching for Sylvie Lee, by Jean Kwok and just finished Jenna Blum’s Woodrow on the Bench: Life Lessons From a Wise Old Dog.

What advice would you give writers and aspiring novelists?

The success is in the writing and doing the work every day. Publication is such a long shot these days and usually not what you think it’s going to be.

So, when you’re writing a novel, it’s for you. Don’t think about whether it’s going to sell, but what it is you’re trying to say. With 10,000 Hills, it’s whether there can be grace when forgiveness isn’t possible. With Come As You Are, it’s whether you can you let go of childhood dreams to make a better life for your own kids.