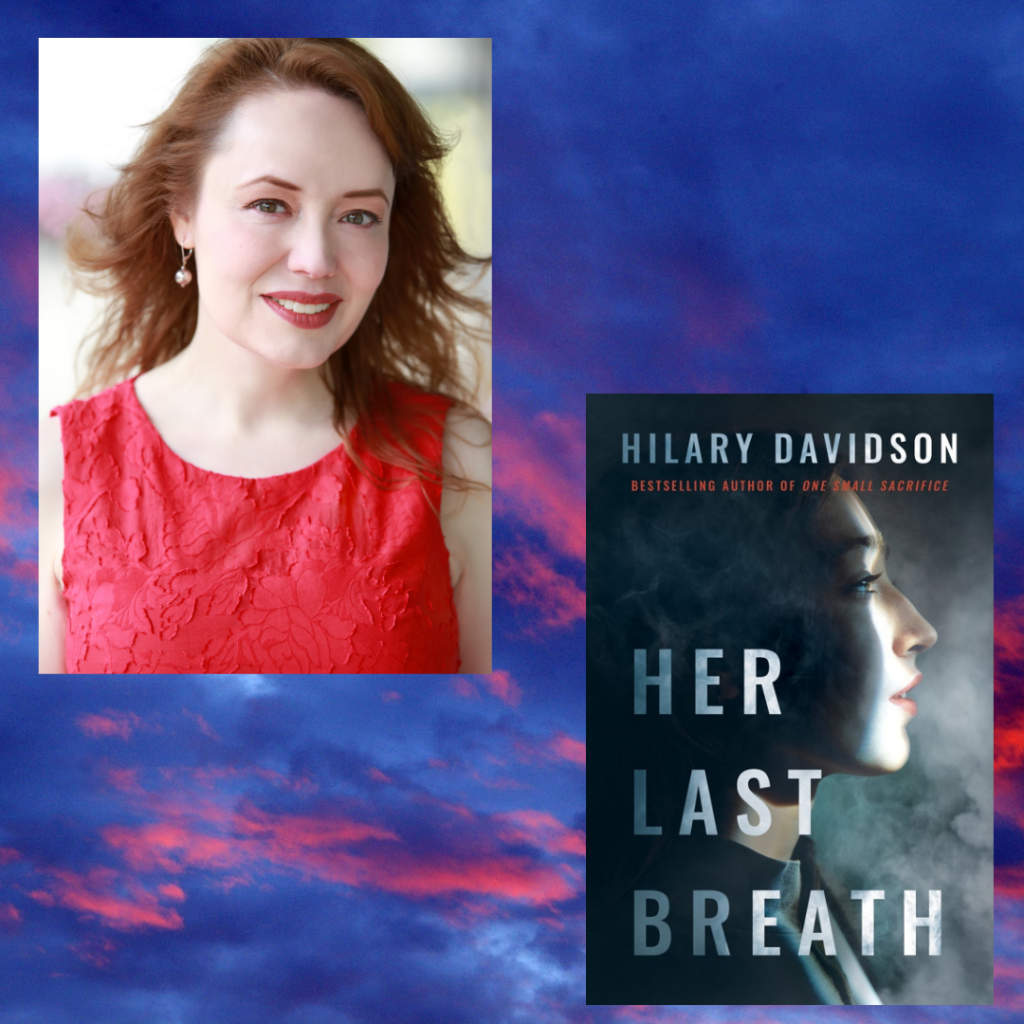

Hilary Davidson is an accomplished New York-based crime writer. Her latest novel, Her Last Breath, has been praised by Bookreporter as “devilishly devious, delightfully scary and edge-of-your-seat thrilling.” Allison Brennan, New York Times bestselling author, described it as “one part thriller, one part domestic suspense, and one part family drama…a fantastic story of love and betrayal, loss and redemption.”

Her Last Breath is Hilary’s seventh novel. Her previous books and short stories have earned numerous awards, including two Anthony Awards—for Best First Novel and Best Short Story—and a Derringer Award for short fiction.

Before turning to fiction, Hilary was a journalist and travel writer, where our paths crossed at several industry conferences. It was a kick to connect once again. Hilary was kind enough to answer my many questions about how her career as a journalist has helped in writing fiction, the value of writing short stories, and how to use setting to enhance a story, among numerous other subjects. She is at the top of her game and her insight is spot on.

How has your career as a former journalist influenced your fiction writing?

The biggest value I learned from being journalist is that you keep writing. Writing fiction is so hard. Self-doubt creeps in. You live with an idea in your head and it seems so great. Then, you put it on paper and it’s not like it was in your head. The golden glow of inspiration disappears.

That’s where the discipline of writing every day comes in. Writing is a job. It’s you sitting down every day and putting words on the page. A journalism background pushes you. You know you have to keep writing.

Journalism also gives you some trust in the writing process. When I’m stuck on the plot I’ll jump ahead, knowing I can research and figure things out as I go along.

Finally, knowing how to research is valuable in itself. As a journalist, you have to contact people who don’t know you and ask questions. In writing fiction, I’ll also reach out to people and ask questions. Most tend to be helpful.

That’s not to say journalism is the best path to writing fiction. People approach fiction from all kinds of paths.

Is it possible to estimate the percentage of plot twists you’ve figured out before you start writing?

At the start, I know the initial setup up and the ending, and I have a strong sense of emotional journey of the main character. But I know maybe just half the plot twists.

I’m failed outliner. I try to outline books; in fact, my current publisher asks for outlines of my books. So I outline, they love it, and then it changes!

However, if I don’t see a plot twist coming, maybe it makes it harder for readers to see it, as well. Crime readers and writers are savvy. They read a lot and they’ve seen many things done before.

I’ve learned to be very organic and forgiving in my writing process. When I write a first draft, I’ll go with my initial inspiration, understanding that I’ll head down some blind alleys and write characters who don’t work out.

My first draft is getting to understand the characters and the things they would or wouldn’t do. I really try to accept what I don’t know and get my ideas on the page so they can become a book. I’m the biggest believer in rewriting. That’s how ideas gel and become a book—and the book becomes good.

I think it’s important for writers to give themselves permission to play with their work and stay open to ideas. I admire people who can stick to outlines, but you have to leave room for fresh ideas.

What do you enjoy about writing series, and what do you like about writing stand-alone novels? (Hilary is the author of the award-winning Lily Moore series—The Damage Done, The Next One to Fall, and Evil in All Its Disguises—the bestselling Shadows of New York series—One Small Sacrifice and Don’t Look Down—as well as the standalone novels Blood Always Tells and Her Last Breath.)

Both have distinct pleasures. With a series, it’s wonderful to write about the world you know. It’s like sitting with old friends. But it also limits what you can do as writer. You can’t kill off your main characters, for example. The reader trusts that they’ll be safe. You have to follow, at least a little, what people expect.

A standalone novel is like stepping onto a tightrope. Anything can happen! It’s thrilling to be in that situation. Right now, I’m keen to do more standalone stories, because of the freedom of creating a new world of characters and throwing them into unfamiliar situations.

One of the things I loved about Her Last Breath was how the setting played such a role, like Deidre’s basement flat and the Thraxtons’ luxurious, if forbidding, apartments and offices. Any tips on incorporating setting into a novel?

In my years as a travel writer, I learned to describe destinations through different lenses. For wedding publications, I’d use more of a romantic, rose-colored view than I would for a story for business travelers.

In fiction writing, I like to think about how setting affects each character and what they see, especially if I’m writing more than one point of view. When I write the same setting through different eyes, what stands out to them?

There’s a temptation to, like author Henry James, take five pages to describe a room. You don’t need that.

I feel description is meant to invoke readers’ senses. So, gargoyles at the entrance to a building can look forbidding, especially if the character is already anxious. You look for things in the setting that mirror the emotional state of the character. It’s a selective representation of what’s there.

What tips would you offer writers who are newer in their journey to publication?

Lots of writers, including me, have an early book in the drawer. It’s hard to get an agent and get attention.

I stepped back after that first book and started thinking about how I could break in. Do I spend a couple years pitching or try something different?

I decided to try writing short stories. My first short story rejected by everyone until I sent it to a crime fiction website, Thuglit. After they published it, the story ended up in a best-of-the-year anthology. That attracted some notice, and led agents to approach me.

Short stories opened the publishing door for me. This was shortcut in the system and an incredible gateway to the next step in my career. They’re a wonderful showcase for writer’s talent.

If you’re interested, give it a try. If a story does well, it can lead to professional interest.

I still write short stories. They’re my playground.

Also, join associations. For me, it’s Sisters in Crime, founded by legendary mystery writer Sara Paretsky. She established the organization because the work of female crime writers had been overlooked. It’s wonderfully supportive and nurtures new writers, both male and female.

How is crime writing changing?

It’s grown to be lot more inclusive of different groups of people, and to also include a greater focus on social justice. Now, the focus isn’t always on the crime, but sometimes on the fallout from the crime and its effect on families. It’s really evolved as a genre.

A less serious question: who would you invite to a book club or writing group?

My first wish would be to get my family all back in one place! In terms of historical icons, writer Oscar Wilde tops my list. I discovered his writing as teen and still adore his fabulous, pointed wit and brilliance.

What’s on your TBR?

I’m reading Runner, the fourth book in Tracy Clark’s mystery series about a Chicago PI, as well as The Turnout by Megan Abbott, one of my favorite writers.